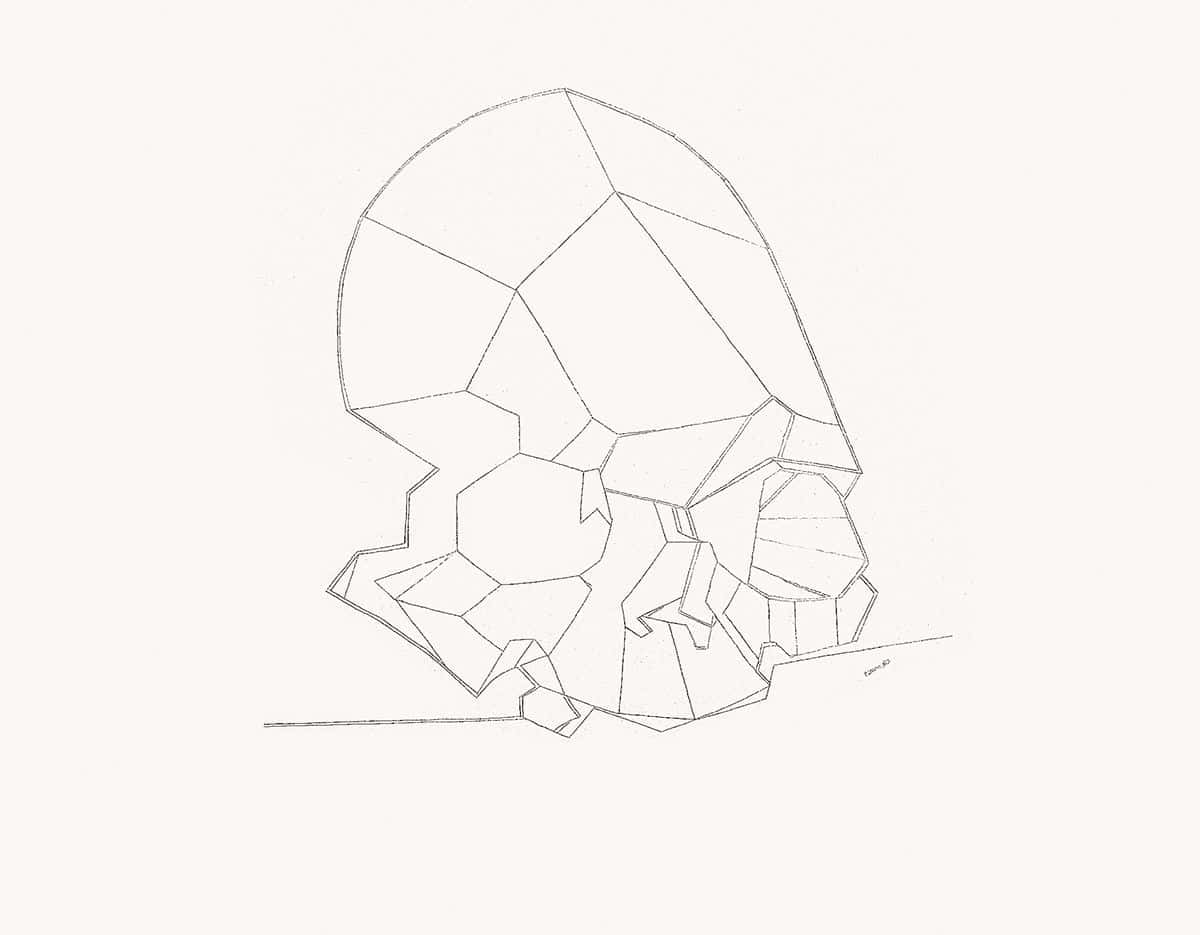

Skull [Cráneo]

Luis Fernández

Skull [Cráneo], ca. 1953

© Luis Fernández, VEGAP. Madrid, 2021

© Fundación MAPFRE COLLECTIONS

Technique

Graphite on paper

Dimensions

Printed area: 50 x 65.5 cm (19 11/16 x 25 13/16 in.)

Frame size: 75 x 90 x 4 cm

Inventory

FM000281

Description

Given that he was born in 1900, Fernández should have been a Spanish artist of the Generation of ’27, associated with the Paris School. But strictly speaking he was neither of those things. Because of the way he was, and the way he behaved, he needed to emancipate himself both from any kind of group proposal and the prevailing discourse on modernity. From the 1940s he was able to crystallize his own truly individual style, and his work, always akin to the style known as la petite manière, without establishing any degree of distance between drawing and painting, sought the constructive presence of the encounter between form and figure.

The iconography of this drawing is the same as that of the other two works on the same subject dated in 1953: one is currently in a private French collection and the other is a well-known oil on wood in the Telefónica Collection. As far as Fernández was concerned, there was no difference in value according to the technique used, but perhaps it is in this drawing that we can best appreciate the complex and solvent structural sense of his compositions. Fernández approached a good number of his compositions at this time by making very elaborate preliminary sketches that are reminiscent of non-Euclidian geometry problems or industrial designs for precision objects. Every plane or surface – according to how the artist himself named them – was given an irreplaceable meaning in the planning sense in these sketches. Chance was thus eliminated from both the conception and the realization, and Fernández sought to achieve an absolute emotional distance from both the subject matter and the sensory energy given off by the physical and mental action of painting or drawing.

The emotional distancing that Fernández advocated should have separated the understanding of his work from any symbolic interpretation, and yet this has not been the case. By using the term ‘sacred’ when referring to the artist, María Zambrano would open the way to an allegorical vision of his compositions. Another interesting aspect is the relationship established by Luis Feás between Fernández’s work and Freemasonic symbolism, according to which the skulls painted by the artist would be associated with certain metaphors of the mind and spiritual life; the skull would symbolize the emergence of an initiatory cycle in which death is the prelude to rebirth at a higher level of life where the spirit would prevail. Whatever the case, when contemplating Fernández’s skulls, perhaps two suggestions should be put forward: on the one hand, the appearance a little earlier in Picasso’s work of skulls and craniums which the artist was not using in the period immediately before Cubism was developed; and on the other, the writings of Fernández himself. In one of the enunciations of his Anhelos (Longings), we read: “Skull at the foot of the Cross, the head of Christ on the Cross, human like the Christ of Perpignan”. This skull at the foot of the Cross has two references: one is that of Mount Golgotha itself, since Golgotha in Hebrew means skull, and the redundant and amphibological effect of the word is used to convey the symbolism of the sacrifice until the consummation, in the promise of a new life; at the same time, it is a symbolic reference to Adam, whose original sin would be redeemed by the crucifixion of Christ. On the other hand, the Christ of Perpignan to which Fernández refers could be that of the Collegiate Church of Sainte-Jean in the French-Catalan city, a figure with a particularly noble presence in the acceptance of suffering, whose carving displays a bold formal synthesis that must have interested the artist.

It is tempting to relate the life and work of Fernández with the concept of conquering the truth through the nobility of suffering, or the possibility of restituting the Adamic; but as Valeriano Bozal pointed out in reference to an interpretation of Fernández’s oeuvre: everything is still provisional.

[Eugenio Carmona]

BOZAL, Valeriano, y BOZAL, Leyre, Luis Fernández, cat. exp. Segovia, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Esteban Vicente, 2005.

CALLE, Román de la, Luis Fernández, cat. exp. Valencia, Galería Luis Adelantado, 1991.

GARCÍA, Manuel, Luis Fernández, cat. exp. Valencia, Galería Luis Adelantado, 1990.

MAS HERNÁNDEZ, Ana, Luis Fernández: primera catalogación de la obra. Madrid, Fundación Telefónica, 2000.

PALACIO ÁLVAREZ, Alfonso, El pintor Luis Fernández (1900-1973). Oviedo, Museo de Bellas Artes de Asturias, 2008.

PALACIO ÁLVAREZ, Alfonso, El pintor Luis Fernández, encuentro íntimo. Oviedo, Museo de Bellas Artes de Asturias, 2001.

PALACIO ÁLVAREZ, Alfonso, Luis Fernández en el Museo de Bellas Artes de Asturias: dibujos y estampas. Oviedo, Centro Regional de Bellas Artes, 2001.

PALACIO ÁLVAREZ, Alfonso, Luis Fernández. Madrid, Fundación MAPFRE, 2007.

PALACIO ÁLVAREZ, Alfonso, Luis Fernández: catálogo razonado de pinturas, dibujos, grabados y esculturas 1900-1973 / Catalogue raisonné of paintings, drawings, engravings and sculptures 1900-1973. Oviedo, Madrid, Museo de Bellas Artes de Asturias, Fundación Azcona, 2010.