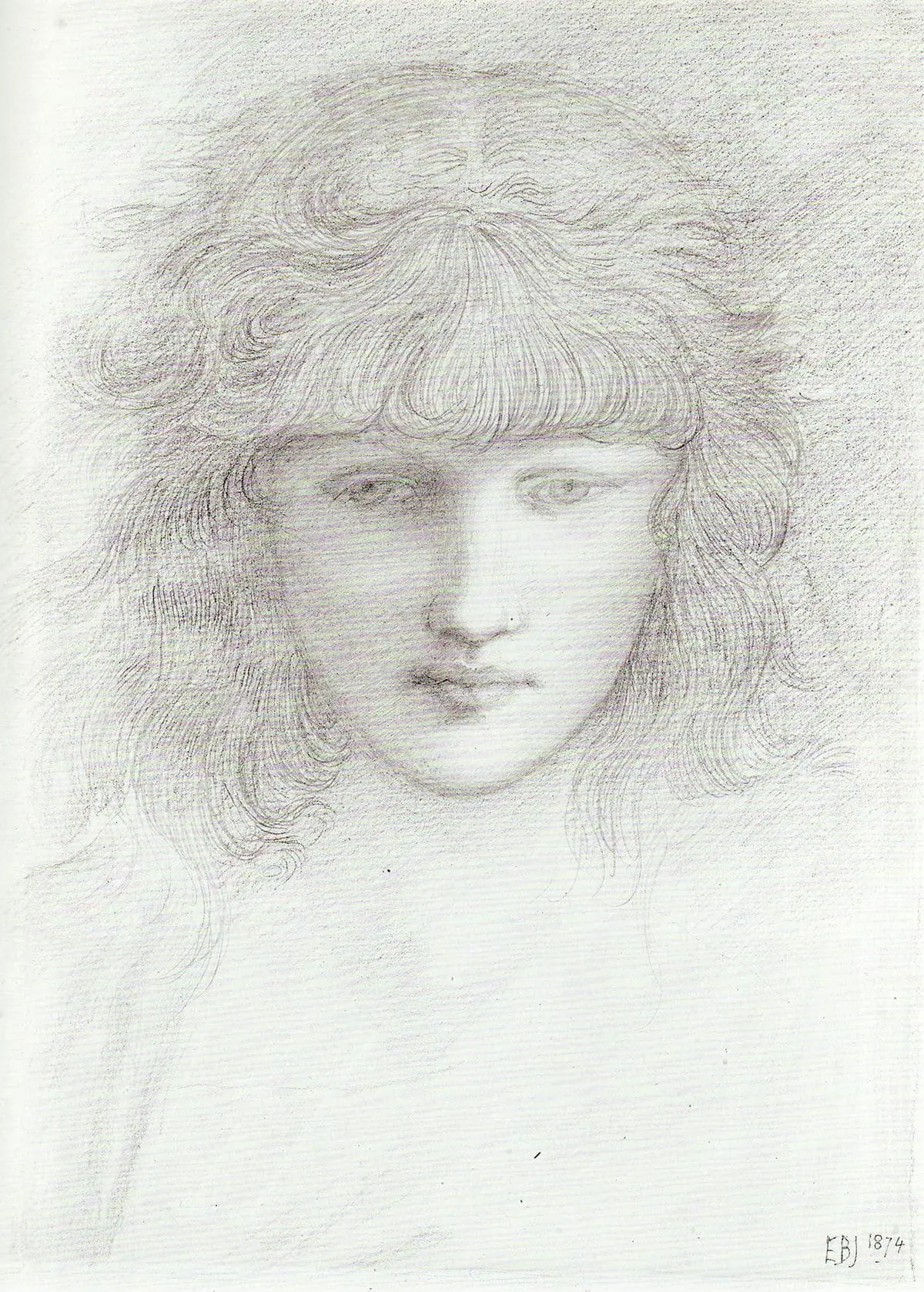

Portrait of a Young Woman, Possibly María Zambaco [Retrato de una joven, posiblemente María Zambaco]

Edward Burne-Jones

Portrait of a Young Woman, Possibly María Zambaco [Retrato de una joven, posiblemente María Zambaco], 1874

© Fundación MAPFRE COLLECTIONS

Entry date: 2011

Origin: Private collection, Great Britain / Piccadilly Gallery, London / Private collection, USA. / Stephen Ongpin Fine Arts, London

Technique

Pencil on paper

Dimensions

With passepartout: 28 × 21 cm (11 × 8 1/4 in.)

With frame: 48,5 × 41,5 cm (19 1/8 × 16 5/16 in.)

Inventory

FM002032

Description

In the mid-19th century, an artistic style appeared in England that would revolutionize how we look at the world: the Pre-Raphaelites. Its most well-known members, among whom Dante Gabriel Rossetti, generally considered its founder, stood out, were fascinated by the works of the Italian Renaissance prior to Raphael, to whom the group owes its name. They would soon dominate the British artistic scene, anticipating with their feminine models some of the prototypes that Decadentism and Symbolism would later popularize.

In fact, if there is anything that characterizes the Pre-Raphaelites, besides their extreme naturalism –their passion for “painting from nature” evidenced in their representations of flowers and plants–, it is their codifications of a type of woman, sometimes embedded in a certain childish ambiguity, such as in this drawing by one of the most outstanding members of the group, Edward Burne-Jones.

The charismatic creator of such popular works as The Golden Stairs (1880; London, Tate Britain), after several initial years under the undeniable influence of Rossetti, Burne-Jones began working on his large narrative cycles, where his signature melancholy women dominate highly theatrical scenes. These women embody an ideal of adolescent beauty, starting with Mademoiselle de Maupin (1835) by Théofile Gautier, a work in which the two sexes are blurred, in clear reference to the undifferentiated androgynous beauty of Helen and Paris. It is an ideal type that hints at incest between siblings, to people joined by the subtle links of parentage, as Mario Praz explains, and which recur throughout the works of Algernon Charles Swinburne, Gustave Moureau, Fernand Khnopff and Burne-Jones. It is also concerned with the eternal debate between the ethereal ideal of the north and the fiery ideal of the south that Gautier addresses in his struggle to decide between the blonde and vulnerable Nordic woman (the “femme frêle“with roots in Romanticism) and the sexually aggressive woman who co-exists with her throughout the second half of the century (the dark Latina). The first, the prototype of the refined woman, half girl, half angel, raises the question of class. It refers to women of the aristocracy or upper bourgeoisie, who often wore light suits, ensuring those nagging colds that Jane Austen often commented on in her novels. This prototype is embodied in the ideal of the sickly woman, or even dead woman, so popular throughout the 1800s: innumerable Ophelias possessing a mortuary beauty transmit the persistent ideal according to which in dying young, one preserves her beauty, in the same way as Christian martyrs die untouched by pain and immune to the ravages of time. This ideal of beauty is embodied most definitively in Elizabeth Siddal, adored by John Ruskin, the fragile muse of the Pre-Raphaelites and, to a certain extent, the antithesis of the passionate Jane Morris, Rossetti’s muse.

These feminine ideals, which often take the form of the immovable and remote sphinx, are the typical notions created by and for men, as Anthea Callen states in her discussion of the Pre-Raphaelites. At the same time, they reflect a generation, a certain young elite, immersed in the cult of the dead and melancholia and that, in contrast to Émile Zola, do not accept bourgeois habits without asking questions.

The beauty of the women that Burne-Jones depicts in this drawing –possibly María Zambaco from Greece, his model and lover and with whom he had a very tempestuous relationship – symbolizes the interesting hybrid of the two types of beauty. An embodiment of the intense dark woman, it reveals at the same time a certain ambiguity, almost melancholic, that reappears in some of the female representations in the artist’s paintings. In this highly delicate piece, Burne-Jones offers viewers much more than a preparatory drawing. For the artist –who soon would substitute his religious inclinations with painting, in which he immersed himself devoutly and through which he expressed part of the spiritual urge inside of him– his pencil drawings have a life of their own. They were the perfect gift for his friends as well as the centerpiece of exhibitions. Burne-Jones was a consummate illustrator, as can be seen in his large paintings, dominated by line vis-a-vis color. It is everywhere: each flower, each fold, each corner of the elaborate architectures of his paintings embody this passion, just as this little drawing does.

Estrella de Diego

ASH, Rusell. Sir Edward Burne-Jones. London, 1995.

BENEDETTI, Maria Terese. «Khnopff e Burne-Jones», en Storia dell´arte, n.º 43 (1981), pp. 263-270.

BENEDETTI, Maria Teresa. «I mosaici di Burne-Jones nella Chiesa di San Paolo entro le mura a Roma», en Paragone (1978), pp. 40-60.

BENEDETTI, Maria Teresa. «Nazareni e preraffaelliti, un nodo della cultura del XIX secolo», en Bollettino d´arte, n.º 14 (1982), pp. 121-144.

BENEDETTI, Maria Teresa y Gianna PIANTONI, Burne-Jones: dal preraffaellismo al simbolismo [cat. exp. Roma, Galleria nazionale d’arte moderna]. Milán, Mazzotta, 1986.

Burne-Jones: The Paintings, Graphic and Decorative Work of Sir Edward Burne-Jones, 1833-98 [cat. exp. London, Hayward Gallery and other spaces]. The Arts Council of Great Britain, 1975.

BURNE-JONES, Georgiana. Lady. Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones, 2 vols. New York, Macmillan, 1904.

CARTWRIGHT, Julia. The Life and Work of Sir Edward Burne-Jones, in Art Journal, special issue (December 1984).

CHRISTIAN, John et. al. Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898): Un Maître anglais de l’imaginaire (1833-1898) [ex. cat. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998; Birmingham, The Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery and París, Musée d’Orsay, 1999]. París, Réunion des musées nationaux, 1998.

FINIZIO, Luigi Paolo. La confraternita dei preraffaelliti. Lineamenti della cultura estetica inglese dal XVIII al XIX secolo. Roma, Cadmo, 1977.

FITGERALD, Penelope. Edward Burne-Jones: a Biography. London, Michael Joseph, 1975.

HARTNOLL, Julian. Burne-Jones et l’influence des Pre-Raphaelites, cat. exp. París, Galerie du Luxembourg, 1972.

IRONSIDE, Robin y GERE, John. Pre-Raphaelite Painters. London, Phaidon, 1948.

LAGO, Mary. Burne-Jones Talking: His Conversations 1895-1898. London, John Murray, 1982.

MARILLIER, Henry Currie. History of the Merton Abbey Tapestry Works. London, Constable, 1927.

MARSH, Jan. Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood. New York, Martin’s Press, 1985.

PHYTHIAN, John Ernest. Burne-Jones. London, M. Kennerley, 1908.

ROSE, Andrea. Pre-Raphaelite Portraits. London, Phaidon, 1992.

SIZERANNE, Robert de la. La peinture anglaise contemporaine. París, 1895.

WILMAN, Stephen (coord.). Edward Burne-Jones: Victorian Artist-Dreamer, ex. cat.. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998.

WOOD, Christopher. The Life and Works of Sir Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898). London, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1998